Sketch Reporting with Off-Ramp’s Mike Sheehan

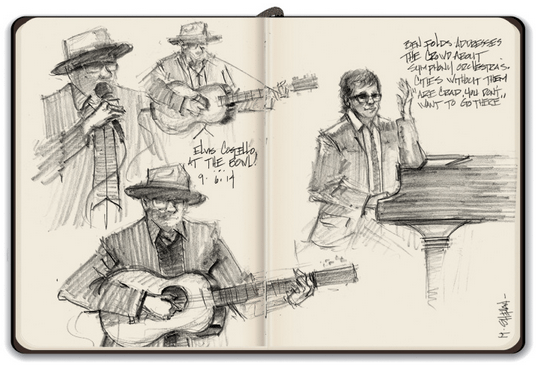

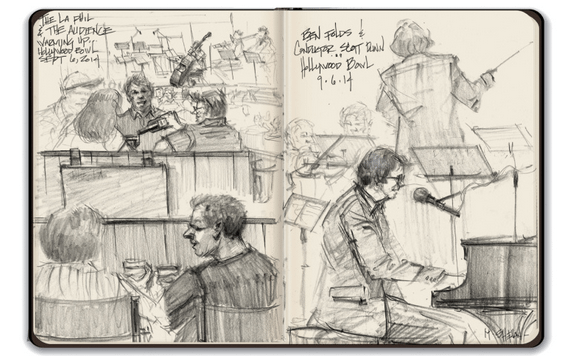

Mike Sheehan may be one of the last great sketch reporters. His contributions for SCPR program Off-Ramp document significant events and stories with a nuance forgotten with photography and a craft rarely cultivated. A former toy designer for numerous big-name companies, Sheehan in recent years has been sketching and reporting nearly full-time, working with Off-Ramp for over two years.

We talked to Mr. Sheehan about his love of sketching, the unique perceptions that sketch reporting affords, and his affinity for Blackwing pencils.

How did you hook up with Off-Ramp?

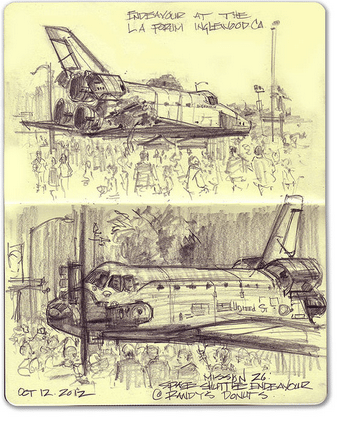

I’ve been working with John [Rabe, host] for over two years. I heard about the [Endeavor] space shuttle coming in, so I went down there and took some sketches…John saw me sketching and talked to me about putting them into his article. He emailed me and I had all these sketches that he ended up using. Since then I’ve gone out and covered some other things, like the Murrieta protests, the symphony…

Where are you based?

I’m mostly based out of home now. I travel to L.A. when I do stuff for Off-Ramp.

What work were you doing before you got involved with Off-Ramp?

I did toy design for 10-12 years. I worked in-house for Disney on their California project, Mattel, Sony, I did toys for Jack in the Box – all kinds of stuff. It’s mostly freelance now.

Was it a conscious decision to begin sketching? Would you consider sketching your full-time occupation now?

It’s definitely becoming more of what I do now. I think I always had an interest in sketch reporting, but when photography came along that went by the wayside. New technologies tend to eliminate the old ones, but I think that people are starting to realize that sketch reporting gives reporting a different perspective – it’s never going to replace photography, but I think it has value as an alternative to photography.

I’m just an obsessive sketcher, you know? If I sit down for five minutes, I’m sketching. It’s like a smoking habit, where it becomes a physical thing. I don’t smoke, but that’s what it’s like – it’s this compulsive thing I’m always doing.

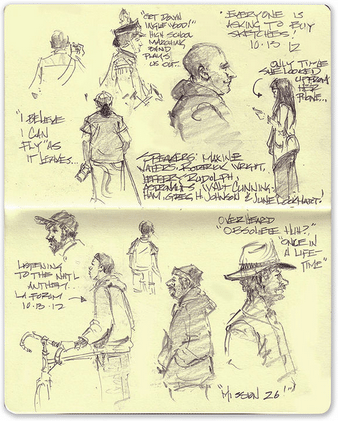

I was in Murrieta, you know – there’s nothing out there but the desert. I was out there reporting for the immigration protest for Off-Ramp. I get outta the car and immediately sit down and spend ten minutes drawing a bunch of people crowded around this area. The rest of the time I’m standing up with my sketchbook in my arm. I can’t really bring luggage out there, I have to know what I’m doing into. Like I said, in Murrieta I only brought a sketchbook and a cabby around it.

Same with the Wendy Greuel event – I had my sketchbook in the crook of my arm. My arm hurt for two or three days after that because I was chasing her around. She’s not going to pose for me – I’m sketching on the fly.

So you have to get these sketches on the quick. Is that a skill you’ve developed over the years?

Yeah. A lot of it’s editing. There are things I’ve noticed that determine what a person looks like, too. Usually the first sketch or two are of the mechanics of a person’s face. It’s like how there are differences between the body of a truck and a car. Once I can get the mechanics of the face down, I can sketch that person even when they change perspective and end up with a different perspective than what I started with. Because people aren’t going to stand still for you, you know?

How important are warm-ups to an intensive day of fast sketching?

Very important. I probably get in five warm-up sketches before I really get going for the day. That’s something I’m always pushing on students – you have to get your warm-ups out. A lot of students’ first sketches usually suck, and then they get discouraged and stop altogether. But you always have to warm up. You have to go into that first sketch with low expectations. I’m never expecting my first sketch to turn out as a keeper, but sometimes the first sketch works out – like with the Murrieta protest. That was a warm-up sketch.

You mentioned earlier that there’s a difference between sketching and photography. Can you elaborate on that sentiment?

Sketching and photography are two different things. I love photography, and I’d probably do it if I weren’t so bad at it [laughs]. But it’s completely different from sketching.

Photography you’re instantly capturing the moment in seconds, whereas with sketching you’re sitting and absorbing the earth for anywhere from ten seconds to two minutes. With that vital pause in time I hear conversations and it gives me a sort of reflection.

I’ve gotten pretty fast at sketching, though. I know what people are going to do – it’s like a weird extra sense. At the Murrieta protest, I noticed this guy in was going to hit a certain pose, because I could tell that he was just one of those angry people that goes to a rally to get fired up and yell. He was talking to someone and he hit that pose – back arched, bowed arms – and I wanted to capture it, but I also wanted to catch the people with picket signs across the way. I took a few broad curves to outline the pose and moved on to something else I saw. Some things are like sketching the tree in the background – it’s always going to be there. I knew this guy was going to get into his pose again and I could fill in the details.

I’m always juggling three to four sketches of people at a time and I can tell which ones are going to come back to certain poses.

So you’re capturing the liveliest things in the moment.

Well, I go in to a site with no preconceived idea. I can’t go back in like half an hour so I’m just trying to capture what I see.

At the end of the day, I’ve absorbed so much. I’m always hyper-aware when I’m sketching. Since I know I have to get something, I’m always looking out and taking in everything around me. It’s an unnatural state. At the end of the day, I come out realizing that it was about something besides what I thought it would be. Like at the Murrieta protests – I went in thinking it would be constructive, you know, people trying to make solutions for the immigration problems. At the end of the day I realized that it was a pointless shouting match where each side is demonizing the other without trying to resolve anything. I didn’t realize that the people that came to protest were gonna be the ones on complete opposite sides of the spectrum.

When you’re hyper-aware like that, all of the sudden the magical scenes happen. At one point while I was sketching at the National History Museum I noticed a scene like that. I’m not relaxing – I’m constantly looking out.

Another advantage of sketching [as reporting] is that you can stay stealthy. Luckily, people never see sketch artists so they’re never looking at me and nobody knows what I’m doing. When they see a guy scribbling information into a notebook, they mostly think, “that guy’s creepy” and want to get away from me, if anything. I want to be a fly on the wall as much as I can. The interaction needs to be as organic as it can. I don’t want it to be like a reality show where none of these people are acting normal because there’s a reporter.

When did you cultivate an interest in art?

When I was a kid. I’ve been interested in it for as long as I can remember. It was messy, though. Back then it was hard to get information – I had to go to the library, where all they had were hardcore books on classical painting and drawing. In a way, it was good for me. Nowadays art books are all about the eye candy and the pretty pictures. These books had no eye candy – just classicism.

When I was a kid I was obsessed with pens. Every time my parents took me to the store, I would look for different kinds pens – I realized later that what my brain was seeking out was a good marker set. My mind was seeking out the tools I needed before I realized what they were. In that way, I think you’re made for it – you’re hardwired for it.

Was it always sketching for you?

The point of technique is to get so fluent with it that it becomes like talking. That’s why I like sketching. It’s very in the moment. It’s important for me that I can do work spontaneously. I like spontaneity, immediacy and just pure craft.

That’s why I like jazz – it’s pure craft. Those guys know their theory back & forth, so that now it’s just a language. It’s a result of dedication. That spontaneous moment took 34, 35, 36 years to get into.

Plus, the instruments are thoughtfully crafted and I think that warmth and craft [in utensils] is what I’m into.

How did you discover Blackwing pencils?

Well, I’m a recovering art supplies junkie. I’d read about them before they came out again. I’d heard that they were going off for hundreds of dollars a box, and I thought it was laughable. Then they became this mystical thing – are these pencils really that amazing? When I heard they were being reissued, I thought, well, I’d try it. When I did, it was like, ‘boom.’ They were perfect for my sketch reporting. The Blackwing is velvety, almost like a charcoal pencil without the harshness of the mark. You can really get a full range of line value out of the Blackwing, from light to dark and dense in one tool.

With what I’m doing – Ideally I want to use one tool if I can. Some artists have their whole set of pencils, from 9H, to HB, whatever, and they have to pull them all out to get something done. I don’t rely on that kind of crap. I want one thing I can rely on. It gives the drawings a sense of continuity.

It sounds dumb, but it’s true: the feeling of a pencil is so important. How a pencil rolls across the page – that’s huge. That makes me want to draw. It’s like oil – it makes me feel luxurious. It feels like butter, man. With the Blackwing you can kind of paint, too. You can get those broad strokes and go back into it for the details.

It even holds its point longer. With the Blackwing, I usually don’t have to sharpen it as often, which is good for my work because I can carry less of them.

I was writing with it the other week and I understood why so many writers swear by it – it’s dense and it still erases. Usually something that writes that dense doesn’t want to erase, but with the Blackwing you have no problem.

I had a student at a workshop I was teaching look at my pencil and ask me, “What kind of pencil is that?” and I told her all of that.