Our Day with Steinbeck

– by Grant Christensen and Alexander Poirier

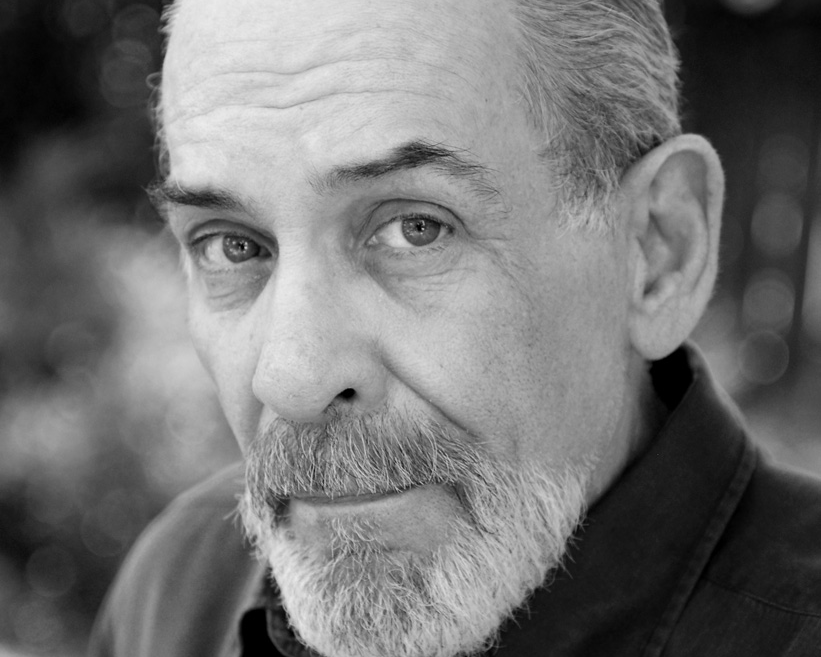

He entered the room with a presence befitting of his pedigree. His slicked-back hair and low-cropped beard had long since conceded their color, but his eyes were still piercing blue. His baritone was rugged but gentle: “I understand you’ve come here to talk about my father.”

John Steinbeck’s eldest and only living son, Thomas J. Steinbeck, wears 71 years with grace, despite decades of battling the after effects of Agent Orange and the Vietnam War. An accomplished author in his own right, Thom had agreed to meet with us to speak about his father, something he has rarely done in recent years. “He doesn’t usually do these types of things,” said his wife Gail, the matriarch of the household. “But your company does a wonderful job, and we want to support you any way we can.”

What we originally expected to be a casual business meeting quickly turned into something much more intimate. Thom’s health prevented him from leaving the house that day, so the Steinbecks invited us into their home where we spent the afternoon surrounded by congenial hospitality, creative spirit, and shelves lined with books.

“Before we get to that,” Thom began, “Have you ever heard the story about how Armand Hammer traded his pencils for the crown jewels of Russia?”

This was the first of many anecdotes and insights we would hear that day. We were even joined at one point by Thom and Gail’s nephew, touring musician Johnny Irion and his wife Sarah Lee Guthrie, whose family tree has creative roots as deep as any.

Thom recalled the first time his father met Sarah Lee’s grandfather, Woody Guthrie. “I wish I’d have heard ‘Do Re Mi’ three years sooner, you’d have saved me a novel,” the elder Steinbeck told the American folk hero. “It took me 400 pages to do what you did in two and a half minutes.”

Johnny then asked Thom “Did you ever hear the story about when Woody met Einstein? On a train…” Yes, it was that kind of day.

We asked Thom about the legend that his father used as many as 60 pencils in a single day. Thom answered with an emphatic “No.” After a short pause, his eyes lit up with a mischievous twinkle. “Sometimes is was 100. Sometimes even more.”

“My father’s handwriting was painfully small,” Thom continued. It was so small and difficult to decipher that for a large part of his career, there was only one editor in the world who could accurately translate his manuscripts. In order to write on such a small scale while maintaining some semblance of legibility, Steinbeck’s pencils needed to be extremely sharp. “Surgically sharp,” said Thom. “Sharp enough to kill an elk at 300 yards.”

The elder Steinbeck also believed sharpening a pencil was a terrible distraction that interrupted the flow of his writing. He developed a ritual to eliminate this distraction, and build confidence.

Each morning his father would sit down at his writing desk in front of two boxes. After reaching for his yellow legal pad, Steinbeck would gather 24 pencils and begin sharpening them, one at a time, in his prodigious electric pencil sharpener. “It weighed as much as a Chevy. And was just as loud,” remembered Thom.

After all 24 pencils were sharpened, Steinbeck would arrange them, point up, in one of the two boxes. He’d then tap them gently with his fingers to ensure they were all the same length. When satisfied with their uniformity, he would begin writing.

Each pencil would last roughly four to five lines. With every word, John would rotate the pencil ever so slightly, ensuring he was able to extract every thought before it had dulled to the point of dissatisfaction. He would then place the expended pencil in the second box, point side down, and pick up another pencil. He repeated this process until all 24 pencils had dulled, at which point he would sharpen them all again, and begin the routine anew.

We went on to talk briefly about why Blackwing appealed so much to his father. “The wood. And the graphite. The quality more than anything.” Thom also noted that his dad hated erasers on the ends of pencils and the ability to remove erasers from Blackwings might have contributed to his satisfaction. “He thought erasers were the ultimate lack of courage.”

The afternoon continued with tales from Thom’s childhood, including the time he spent in Mexico with his pistolero nanny. He even told us what his father’s perfect pencil would look like.

Thom’s way with words, and striking resemblance to his father, made us feel like the Nobel Laureate himself was in the room. We left our visit feeling energized and empowered, not only by the stories, but by the man who told them. Hopefully the Blackwing 24 will bring others as much inspiration as we felt after our day with Steinbeck.

The Blackwing 24, a tribute to John Steinbeck, is available now. Read more here.