Name: Jason Patterson

Pencil hand: Left

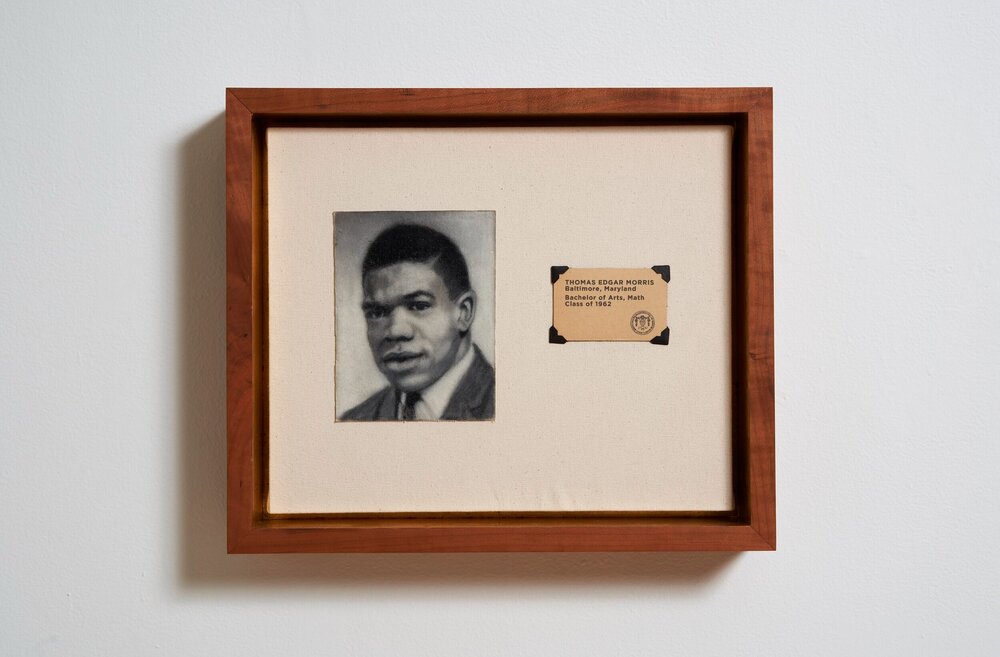

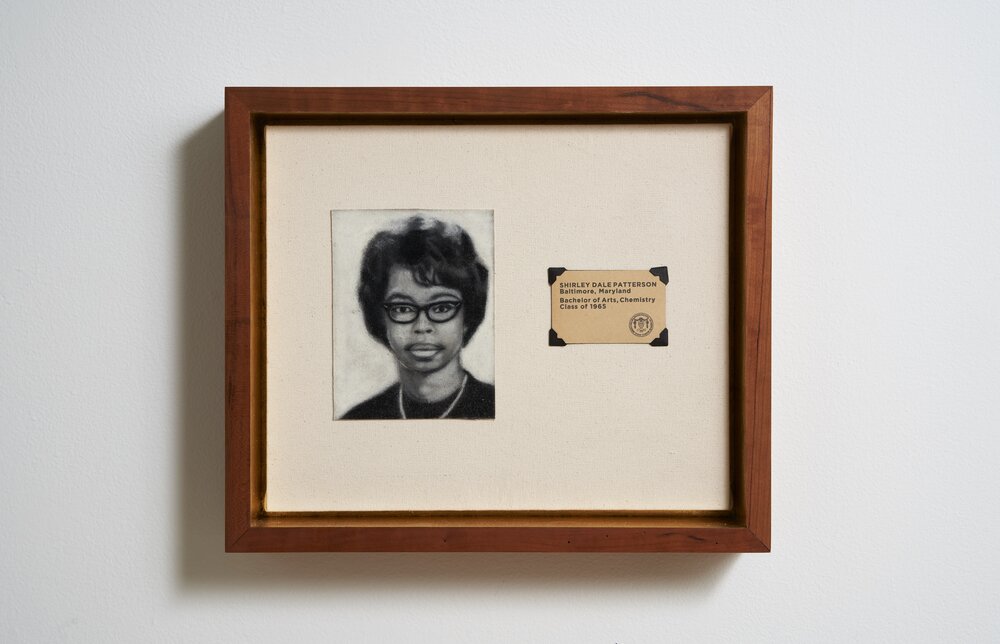

Craft: Portraiture/Woodworking/

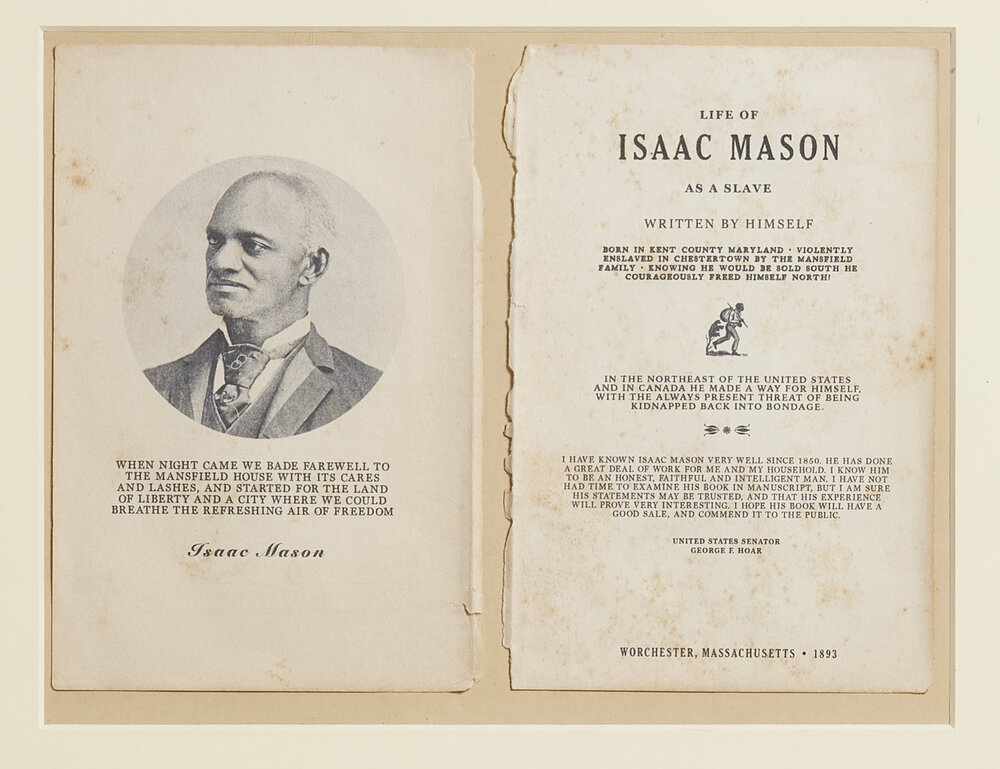

Re-creation of historical documents

Location: Chestertown, Maryland

“I believe when I create artwork it’s a special way to keep people interested in that history I’m presenting. The philosophy that drives me is the idea of contributing to society. I think of my work as educational resources that will help all of us better know our past so we can better understand our present.”

THE PROCESS

We had the opportunity to sit down for a chat with portrait artist and woodworker Jason Patterson. Using historical documents and meticulous research, Jason’s transformative work is centered around telling stories of African American history from his local community on the eastern shore of Maryland and beyond.

Can you tell us a little about your craft and how you got into it?

Ever since I was a small child I drew portraits of people. As I grew up the two subjects that stuck with me the most were art and history, and in my 20s I combined the two. Over the years I’ve been greatly influenced by historians for subject matter. And I’ve also been heavily influenced by a group of engineers who are close friends of mine. Their work ethic and style of problem-solving were very adaptable to my studio practice. Those same engineers also introduced me to woodworking. About 10 years ago I had the idea of making decorative frames for portraits that I was planning on doing. With their help, I was able to learn basic woodworking and turn that skill into a standard aspect of my practice: creating stylized and period-based frames for my portraits and eventually my historical documents.

For my historical documents, I got into this because when I do my research and go through old books I find important texts, and find their formatting to be quite beautiful. And sometimes you only really need those words to convey the historical narrative you’re trying to tell. Also, often there are no photographs or usable images from that time period. So, this led me to re-creating historical documents and/or creating originally designed documents with actual historical text in them.

How did your interest in history influence your artwork?

I’d never been good at school, but I knew that I was good at art and loved history. Around 2006/2007, I’d dropped out of community college and wanted to focus on becoming an artist. A big influence for me was the landscape painter from Chicago named Don Pollack, who became a good friend and mentor to me. His work is focused on American history and uses historical research as a reference for his paintings. Meeting him really solidified what I wanted to do, and helped me land on African American history as my focus.

How do you approach your process?

A lot of the time, I’ll be reading a book or a historical text and I’ll discover something that really has a contemporary parallel and relates to our present moment. Other times, I’ll be researching a subject, which then, in turn, opens me up to a different subject entirely, which then becomes the start of a future project. When I make this work, what is really important to me is not to shock or trigger the viewer because I do not want to alienate anyone. I’m not so concerned about changing peoples’ minds, as much as I want them to just consider the presented history and to think about it.

The goal is, how do I use my skills in art and woodworking, to make compelling work that tells people about Black history. I think about how museums and institutions present work publicly, and in a way, I try to emulate that. I try to create visually appealing artwork. The hope is that when the work draws people in it will get them to think about the history that’s being presented.

A selection of Jason’s work featuring portraits of Frederick Douglass, Fred Hampton, and a re-creation of pages from William Still’s 1872 published record The Underground Rail Road.

How has your location played a role in the stories you tell?

I lived in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois for the first 33 years of my life and when I moved to the eastern shore of Maryland, almost 4 years ago, it seemed like fate because this area is rich in African-American history, but much of it is relatively unknown. Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass are from here, and most people stop there. But there is an overwhelming amount of important African-American history that happened in this unique region of Maryland.

Do you think viewing things within a historical framework is able to give them a greater impact?

When I do this research and I read something from 100 or 200 years ago, I do see that history repeats itself. People don’t often take that cliche phrase seriously (which is understandable), but it’s fundamentally true. For me, if you can see the similarities between what we’ve done in the past and what is happening now, it can be a great help in the effort to do the right thing when dealing with our present issues and struggles.

I made a piece that references Rosa Parks’ time in Detroit. I feel like she’s one of the most misunderstood and poorly represented historical figures of the Civil Rights Movement. She’s often portrayed as a weak old lady that just randomly decided to resist, but her refusal to get out of her bus seat was a planned effort from her and the NAACP to initiate the Montgomery Bus Boycott. She was only in her early 40s, a seasoned activist and civil rights leader who had significant roles in the Montgomery and Alabama branches of the NAACP. After her arrest and the bus boycott, she lived the rest of her life in Detroit after being basically forced out of the South. What I try to do with my work is to tell these relatively lesser-known parts of history and shed a light on them.

Jason’s work focusing on Rosa Parks’ time in Detroit

What inspires you and what informs your work?

What inspires me is the research aspect of my work. When I go through historical texts I find history that I think is important for people to know, but isn’t actually well known. That inspires me to make work about it to bring to the public. I believe when I create artwork it’s a special way to keep people interested in that history I’m presenting. The philosophy that drives me is the idea of contributing to society. I think of my work as educational resources that will help all of us better know our past so we can better understand our present.

What are some things that you find quintessential to your creative process?

For me, it’s research and planning. I do a lot of historical research in archives and reading historical texts, where I take a lot of notes. In my studio, and especially with woodworking, I draw out a lot of plans and write down ideas. And this is where Blackwings definitely come in!

What is a quote or idea or piece of work that inspires you/drives your creativity?

I don’t know if I have one specific quote or piece of artwork I go back to. But there are a few artists and thinkers that, when I’m in a bind on a project, I go to and read their writings and look at their work. Namely Kerry James Marshall, Gerhard Richter and James Baldwin. With Marshall, the way he’s able to encapsulate black history and culture in single artworks that are so specifically his style — he’s very inspiring and always helps me get to my own ideas. Gerhard Richter’s photo paintings are really the foundation of my portraiture aesthetically. I always go look back at Richter when I’m having trouble with an image. And the way James Baldwin wrote about his time really helps me think better about how I reference our present, through my artwork about our past.

Can you tell us about any recent projects you’ve done that have stood out to you?

The last significant exhibition that I did was at Washington College and supported by the Chesapeake Heartland Project. It’s specifically about the Black history of the college and of Kent County Maryland itself. Washington College was the first college founded after the American Revolution in 1782, and for its’ first 180 years, it did not have any Black students. This is just one example of the college’s long history of white supremacy, that the college is now working to reckon with. I’m proud that my project has been a big part of that work.

Jason Patterson’s exhibit at Washington College supported by the Chesapeake Heartland Project.

How did you find out about Blackwing?

For years, back in Illinois, I worked at an art supply store, in the early 2010s I was a fountain pen person. My buddy Mike Hagan, who used to have the blog LeadFast about pencils, would come into the store to buy art pencils, but for writing. He turned me on to Blackwings (which we sold but I had never took the time to use) and collecting pencils in general — which I, dealing with the high cost and maintenance of fountain pens, was eager to switch over to. I quickly fell in love with wood pencils in general and in particularly Blackwings.

When and why did you start using Blackwing?

As I mentioned before I always take notes in my practice, and I’ve always tried to find really nice writing utensils for this. It’s an interesting story, but one of the reasons why I used fountain pens at first was because I thought if I want things to be preserved over the decades or even centuries, I couldn’t use pencils. What changed my mind about that was doing so much research in archives and finding texts that are 100 years old or more and being able to read the notes that people left that were all written in pencil. So often I joke to people, “pencil only isn’t permanent when you erase it.” I was definitely drawn to Blackwings, not only because of the pencil’s excellent design, and amazing graphite, but also the long and super interesting history behind the pencil.

How has Blackwing become a part of your process?

I really love the softer graphite in Blackwings. So, Along with the reasons mentioned above, the smoothness of the graphite really helps when you have ideas pouring out and need to write fast!

What are some other essential tools you can’t live without?

My MacBook and workable spray fixative. I do so much of my work on my computer in Photoshop before drawing it on canvas or printing it out on vintage paper. I’d really have to change things up if I didn’t have it. The way I create portraits, I use a unique style of soft pastel and charcoal on thick raw canvas. To be able to do this I need to use copious amounts of spray fixative, which I use almost like an art medium. Don’t know what I would do without it!

Are there any pieces of advice that you would give to someone who wants to pursue a future in your line of work?

Stay true to yourself. And do what you love. Now I know how cliché these two things are but it’s true. When you’re an artist you have to put so much of yourself and your time into the work. I don’t know how anyone could do that unless they’re doing what they love. One of the best ways to know whether or not you’re doing what you love is if you still love even the most boring or monotonous part of it. I love stretching canvas just as much as I love drawing pictures on it.

What are some resources you’d recommend for those looking to learn more about African American history?